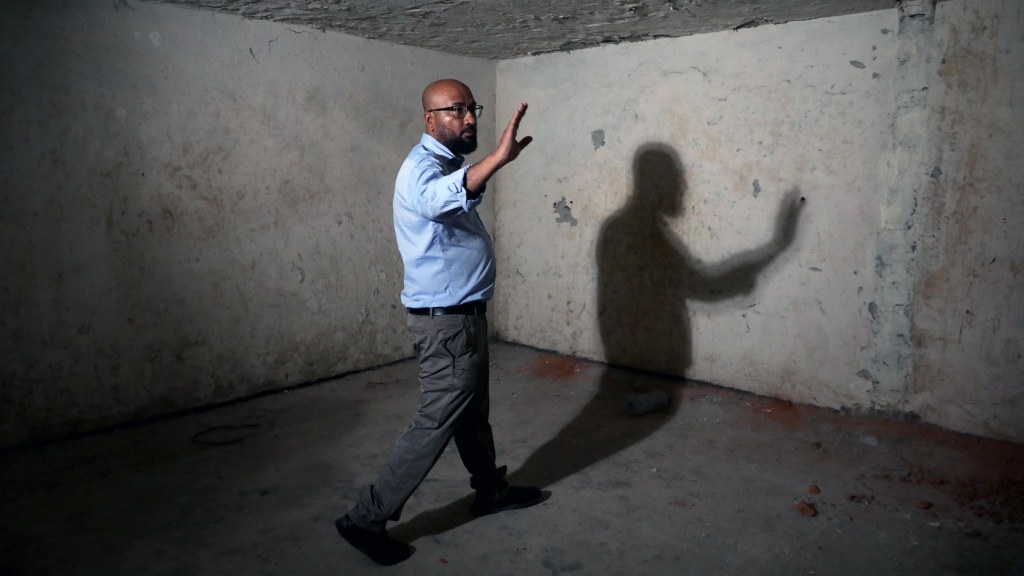

In February 2025, Tasneem Khalil and his team visited secret detention facilities with the Head of State. This photo, taken by Netra News’ Director of Photography Jibon Ahmed, shows Tasneem during the visit.

In February 2025, Tasneem Khalil entered Aynaghar, translated as the House of Mirrors, a secret detention center in Dhaka, Bangladesh’s densely populated capital, operated by an agency commonly referred to as “DGFI,” which stands for the Directorate General of Forces Intelligence. Over the past decades, hundreds of individuals had mysteriously disappeared from this facility, leaving no trace.

Tasneem was not a prisoner this time. He was the only independent editor with a tiny team invited to join Bangladesh’s new interim leader, Nobel Laureate Professor Dr. Muhammad Yunus, on a tour of the torture cells. But the experience was surreal for him, who had endured torture at the hands of the same military intelligence agency 18 years ago, before seeking refuge in Sweden.

“”I think I am likely one of the very few journalists who not only write about torture but also criticize the system and have personally fallen victim to that same oppression. No one can erase that record,” he told One-man Newsroom. “My critics attempt to interpret this differently. They claim that because the DGFI tortured me, I speak out against the agency from a purely personal perspective. That is not true at all,” he added.

Tasneem described himself as an anarchist, “Ideologically, I am strongly opposed to the state system. By default, I criticize the state’s power, particularly its policing and military functions. So, ideologically, I have always been against this system,” he said.

In 2007, amidst a military-backed caretaker government, the inspiring journey of Tasneem Khalil, a Swedish Bangladeshi journalist, unfolded, highlighting his remarkable courage and commitment to truth. At that time, this journalist experienced torture and surveillance by the DGFI, which forced him to leave Bangladesh at the age of 26, taking his six-month-old child and wife with him.

“I am not qualified to evaluate Tasneem Khalil’s journalism,” said Sayed Khan, whose official name is Hafiz Al Asad, the Organizational Secretary of one faction of the Dhaka Union of Journalists (DUJ). He told One-man Newsroom, “As a reporter, however, I understand why Tasneem had to start Netra News. Before that, he was associated with mainstream media here and was a prominent reporter. Yet he could not practice journalism freely in Bangladesh; he was not allowed to. When he could no longer work here, he left the country.”

“Even before founding Netra News, he had tried to continue his reporting in other ways,” Sayed added, “The space for journalism has narrowed not only in Bangladesh but in many countries around the world. That is why outlets like Netra News are emerging. In the context of Bangladesh, it was the first outlet to conduct such in-depth investigative reporting.”

For the first time since the 2024 uprising, the media in Bangladesh are exposing the Deep State’s actions, and calls to abolish the DGFI, and also the notorious elite force Rapid Action Battalion (RAB) are growing, army officers are on trial, and the ousted prime minister Sheikh Hasina is denying responsibility!

Human Rights Watch (HRW) published this photograph of Tasneem Khalil, showing bruises from torture endured during his 2007 detention by the DGFI, taken 48 hours after his release.

📷 HRW

Tasneem Khalil is a key figure in this context. He bravely uncovered secret detention facilities operated by the Hasina administration, with substantial documentary proof. While many mainstream media outlets in Bangladesh chose silence, he took a courageous position.

In August 2022, Netra News disclosed how the military intelligence agency, allegedly acting on orders from a former prime minister, was involved in the clandestine detention of many individuals. In an email interview with the BBC, published on November 14, 2025, Hasina refused to acknowledge personal involvement in secret detention sites or extrajudicial killings.

“This is denied in terms of my own involvement, but if there is evidence of abuse by officials, let us have it examined properly in an impartial, depoliticised process,” she told the BBC.

Later, on November 17, Bangladesh’s International Crimes Tribunal (ICT) sentenced former Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina and former Home Minister Asaduzzaman Khan Kamal to death for crimes against humanity, including alleged “kill orders,” enforced disappearances, and systematic torture, abuses that international investigators say contributed to the deaths of more than 1,400 people.

Stanford University’s Walter H. Shorenstein Asia-Pacific Research Center awarded the 2025 Shorenstein Journalism Award to Sweden-based investigative outlet Netra News, and its founding editor-in-chief, Tasneem Khalil, in recognition of their “courageous reporting” that exposed high-level corruption and human rights abuses in Bangladesh, while defending press freedom and democracy.

In addition to the Shorenstein Award, Tasneem Khalil (and Netra News) has received a 2024 Sigma Award for their “Body Count” investigation, a 2024 Human Rights Press Award for their documentary on RAB’s death squad, and a Global Shining Light Award (Certificate of Excellence) for uncovering secret prisons in Dhaka.

Khandaker Ali Ar Raji, a faculty member of the Department of Communication and Journalism at the University of Chittagong, said, “What Tasneem Khalil has done would have had a significant impact if he had been able to do it in Bangladesh, withinthe local media ecosystem.”

“The first point is that no journalist in Bangladesh has the kind of state-level protection or support that he has. This kind of journalism is only possible for Netra News because it operates in a Scandinavian country. Or for someone like Zulkarnain Saer, who works with institutions like Al Jazeera. But this is not journalism within Bangladesh,” he told One-man Newsroom.

“Some young boys and girls in Bangladesh might dream of working at Netra News, Al Jazeera. Or as Khaled Mohiuddin in Deutsche Welle, or Thikana. However, this is not Bangladeshi journalism; it is journalism about Bangladesh produced by certain journalists,” Ali Ar Raji added. He said, “It’s a form of work, yes, but it does not shape the overall landscape of Bangladeshi journalism. Because first of all, they stand apart due to their identity.”

Tasneem has also acknowledged that, as a Swedish journalist, he enjoys far greater freedom than reporters in Bangladesh. “I deserve the freedom to pursue journalism without any external pressure influencing my work,” he stated.

“You have to understand something; I am a Swedish publisher. And in Sweden, press freedom is especially protected by law. This law is embedded in the Constitution, making it clear that any change requires a formal amendment to the Constitution itself. In that regard, I belong to a protected category. Swedes are inherently free individuals, and I enjoy an even greater level of freedom. No government can exert pressure on me.”

“I know that after certain stories published by Netra News, the Bangladesh government attempted to reach out to the Swedish government. However, they had to immediately cease their efforts. It’s because the Swedish government and the Swedish embassy firmly maintain that they will not take any actions that could even minimally undermine press freedom, including for journalists or the media. Therefore, I do not face any pressure of any kind,” he said.

But, before November 16, 2024, every member of Netra News’s Bangladesh team worked anonymously for safety reasons. After Tasneem’s return to the country, the outlet organized a public event to meet its readers, during which the entire Bangladesh team appeared openly for the first time.

At a reader engagement event after his return to Bangladesh, Tasneem Khalil introduced the Netra News Bangladesh team, who appeared publicly for the first time after years of working anonymously for security reasons. November 16, 2024.

📷 Sharif Khiam Ahmed

During the previous Awami League government, he was labeled a “fake journalist.” Under the controversial Digital Security Act (DSA), cases were filed against him, portraying him as an “anti-state cyber-terrorist” who was supposedly conspiring against the government from abroad. Alongside multiple cases, his only family member living in Bangladesh, his mother, faced relentless harassment.

“My mother had to endure continuous harassment,” Tasneem told One-man Newsroom. ” The US Treasury Department imposed human rights-related sanctions on RAB (December 10, 2021); it decreased somewhat, but the harassment had gone on for years.”

Nazneen Khalil, a renowned poet across the country for decades, had the opportunity to see her son, Tasneem Khalil, in 2025, almost 18 years after their last encounter. However, Tasneem’s father, Khalilur Rahman Qashemi, a prominent figure in literature, culture, and journalism in the Sylhet region, passed away in 2018. He endured the pain of being separated from his son for many years. Tragically, Tasneem could not attend his funeral due to fears of potential consequences from the authorities.

Sayed Khan, the DUJ leader, added, “After Netra News began reporting on Bangladesh, and several of their stories became widely discussed, many accused them of spreading rumours. Some of our fellow journalists called Tasneem a rumour-monger, a troublemaker, an agent of this or that organisation or country, saying he was advancing some foreign agenda.”

Tasneem never backed down, despite the trauma caused by Bangladesh’s law enforcement agencies. He persisted in publishing courageous investigations that exposed serious crimes committed during Sheikh Hasina‘s rule—reports that challenged the very foundations of the previous government. His reporting has helped ignite a rare moment of accountability in Bangladesh.

“Those journalists who attacked him are the ones undermining journalism in Bangladesh. They have engaged in praise-journalism and have not allowed investigative reporters like Tasneem to remain in the country,” Sayed Khan said.

Tasneem said, “Reporters are labelled ‘agents of the intelligence services‘ or ‘in someone’s pocket’ only when there is no legitimate criticism. When people cannot rebut my reporting with reasoned arguments or challenge it on its facts, they tag me instead: ‘He is an agent of this country or that country.’ Rather than obsess over which country’s agent I am, point out any errors in Tasneem’s reporting.”

“For example, imagine that I am an agent of Saudi intelligence. I’ve reported that the military intelligence headquarters in Bangladesh has a concealed detention facility nearby. Where they held individuals for extended periods. Now, does it matter whether I’m an agent of Saudi Arabia, Taiwan, or any other country? That is the question,” the veteran journalist stated.

Sayed Khan told One-man Newsroom, “Netra News is, in my opinion, a shining example of investigative journalism in South Asia today. Suppose more outlets like Netra News emerge and endure challenging times. In that case, I believe we will see improvements in governance and accountability within society.” He said, “Without establishing mechanisms to hold the deep state accountable, we will be unable to restore the rule of law, good governance, human rights, and basic freedoms. We need more journalists like Tasneem Khalil.”

At the height of the July uprising, on July 24, 2024, Sayed Khan was arrested on charges of sabotage. He told One-man Newsroom, “It felt as though they were rescuing some notorious crime lord, the very best terrorist in the city. They threw me into the car, grabbed me from both sides, pulled my arms behind me, and snapped handcuffs on. Then they blindfolded me in an instant.”

“I said, Brother, I’m a journalist. I’m not a criminal. What sense does it make to tie me up like this? I’m not a thief. You haven’t found any weapons on me, nor have you arrested me at the scene of any heinous crime. Why bind me like this? Why blindfold me and cuff my hands behind my back?”

“No sooner had I spoken than, from behind, there were several people seated around that microbus, two sat on either side of me. From behind, someone struck me over the neck at least fifteen to twenty times with a thick, hard object. They hit with such force that it felt as if my eyeballs were about to burst and my teeth were shattering,” Sayed Khan added.

Tasneem Khalil visits the family of Touhidul Islam in Comilla, the Jubo Dal leader who died after being beaten while in army custody. Khalil listened to the family’s account and documented the circumstances surrounding the killing. February 5, 2025.

The journalist who refused to be silent

Tasneem Khalil’s story explores the complex machinery of state terror, what Bangladeshi journalist, academicians, and officials calls the “Deep State,” which remains entrenched even after the fall of the autocratic Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina. After 18 years of being away from the country, during another interim administration, in 2024, following the Nobel Peace Prize laureate and the only Bangladeshi professor to win the prize, Dr. Muhammad Yunus, assuming power, he returned to Dhaka.

Tasneem opened the Dhaka bureau of his Sweden-based news outlet Netra News. Sitting in that office, he told One-man Newsroom, “I am known as very anti-militarist, and I am indeed very anti-militarist. There is nothing to deny about that.”His outlet continues to publish stories that regularly raise questions about the Bangladesh military’s actions. But even under Yunus’s administration, the government has continued to question Netra News’s reporting.

On November 3, 2025, in an official statement, Faisal Hassan, Public Relations Officer of the Ministry of Home Affairs, wrote, “The Government of Bangladesh firmly rejects the recent mischaracterisation of the Chittagong Hill Tracts (CHT) as an ‘occupied’, ‘militarised’ region, or ‘under military rule’, as presented in a recent article by Netra News and its associated photo project. Such descriptions are factually incorrect, misleading, and disrespectful to both the people of the Chittagong Hill Tracts and the Bangladeshi nation as a whole.”

Tasneem told One-man Newsroom, “Which other part of Bangladesh requires army permission to buy rice? But this is the reality in the Chittagong Hill Tracts. On one hand, you say the people of the CHT are full citizens with equal rights; on the other hand, you keep them confined within restrictions. Of course, foreign media will report on this—how can they not?”

In a March 2007 interview with The Washington Post, Tasneem Khalil discussed the military-backed civilian government and Muhammad Yunus‘ political vision. “It may ring untrue, but he is not at odds with the army,” He said, “He may be well intentioned. However, there is a much darker agenda at work here, and Dr. Yunus may be falling into a trap.”

Years later, during an interview with Muhammad Yunus in November 2024, Tasneem informed him that the army was refusing to grant him access to the secret detention facilities. The Head of State promptly assured Khalil that he would secure that access.

Following through on that promise, when Yunus visited the secret detention facilities in February 2025, Netra News, represented by Tasneem Khalil and his small but dedicated team, was the only independent media outlet allowed to accompany him.

For a newsroom that has spent years investigating the hidden layers of state power, Yunus’s trust was a significant validation. This moment not only showcased Netra News’s distinctive courage and credibility in investigative journalism but also marked a historic step in documenting one of the most sensitive chapters of Bangladesh’s human rights crisis.

The Aynaghar visit, initially announced as an open inspection with survivors and the press, had been sharply restricted after objections from senior military officials. Still, Yunus proceeded, describing the scenes inside as “horrifying” and “beyond belief,” pointing to an electric torture chair and multiple sealed cells that he said reflected “some of the worst crimes ever committed.” Survivors outside recounted being abducted, framed, and tortured for years, while Yunus vowed that “those responsible must be held accountable.”

Earlier, reporting from Sweden, Tasneem documented how a military chief close to the head of state and his family obtained illegal privileges, and how army officers serving in the RAB carried out hundreds of extrajudicial killings. As a human rights campaigner, Tasneem has been outspokenly critical of both the RAB and the DGFI for many years, calling for their disbandment.

To One-man Newsroom, he said, “We raised the call to ban or abolish RAB many years ago. It is a significant achievement that the BNP, a major political party in Bangladesh, has now accepted and adopted this demand. Their leadership established RAB, and now they claim they will abolish it if they regain power.”

“This is a process,” he continued. “It’s important to understand that there won’t always be mass protests or movements on these issues. Mass movements typically arise around significant problems, such as public-sector job quotas, which significantly impact the daily lives of millions of people. However, human rights issues tend to generate less widespread mobilization. But the DGFI should be dismantled. And it is only a matter of time until the agency comes to an end.”

In February 2025, the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) recommended the disbanding of RAB, citing years of extrajudicial killings, enforced disappearances, and widespread abuse. The report further advises that the DGFI be limited to military intelligence activities only.

Responding to questions at the ministry on December 10, the Adviser for Foreign Affairs, Md. Touhid Hossain said that institutions like the DGFI exist in every country. Decisions on reforms or abolition will depend on what the current and successive governments deem acceptable. “The OHCHR provided 40 recommendations. We will implement those that we find acceptable, as well as those that the next government agrees on. There is no obligation to fulfill all of them,” he added.

The adviser remarked that RAB has seen “significant changes” and was once “a highly effective institution.” Still, it has been “damaged over the last 15 years.” He emphasized that if RAB operates more responsibly in the national interest, “there is no need to destroy the institution.” He dismissed new sanctions for human rights violations, citing no new allegations and “clear improvement” in RAB’s activities. Regarding existing US sanctions, he noted that the matter is “under process.”

A few months earlier, rejecting speculation that the government planned to dissolve the DGFI, the Chief Advisor’s Press Secretary, Shafiqul Alam, said the administration was only considering reforms to strengthen its focus on cross-border and foreign intelligence operations. His statement followed a military briefing on October 11, during which the army confirmed the arrest of 15 officers named in warrants for alleged enforced disappearances, torture, and other crimes against humanity committed during the Awami League administration. Among them, 13 officers served RAB and DGFI.

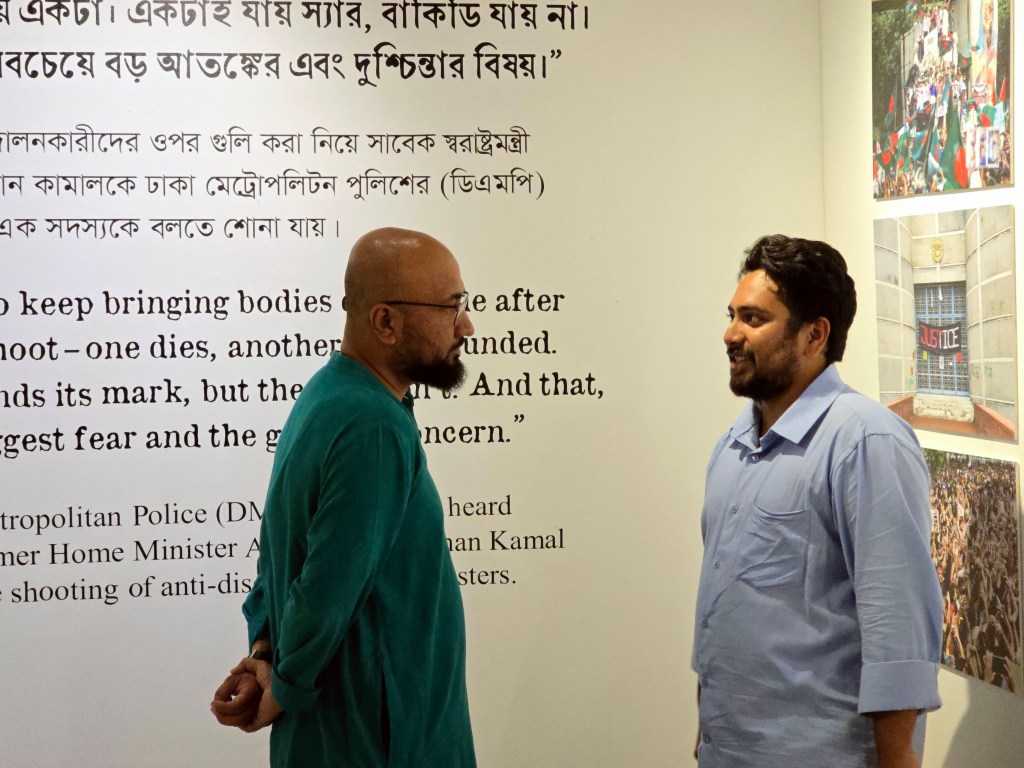

Tasnim Khalil is with Ehsan Mahmud, who works undercover for Netra News in Dhaka. November 19, 2024.

📷 Sharif Khiam Ahmed

Tasneem Khalil, the author of the book Death Squad and State Terror in South Asia, added: “In every democratic country in the world, there is a national intelligence agency, and it is under civilian control. It is a professional intelligence service, for example, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) in the US, India’s Research and Analysis Wing (RAW), and similar organizations in other countries, such as France and Sweden. Every country has such an intelligence agency.”

“But DGFI, a military appendant intelligence agency, interferes in civilian politics, civilian culture, civilian banking, and civilian journalism. It even happened that DGFI colonels used to sit in the High Court and the Supreme Court. They had offices there. They drafted judgments, meaning they wrote rulings that judges had to read and follow. It’s happened in Bangladesh. You would only otherwise find such precedents in Pakistan. DGFI is simply the notorious ISI’s Bangladeshi version,” the investigative journalist added.

At an event on May 3, Shafiqul Alam also said, “The worst thing that has happened in the past 16 years is that our security agencies have acted like private mercenaries. I personally know of two or three cases where an industrialist or businessman employed DGFI officers to intimidate judges in court. They would pressure the judges, insisting that a specific individual should not be granted bail and warning them of consequences if they did.”

Teacher and researcher Ali Ar Raji said, “The concept of a ‘deep state’ often comes up, particularly in discussions about our military. The military cannot operate freely across the country. Military officers, like everyone else, have family, friends, and siblings. They live in fear of being reported, as any negative report could jeopardize their entire careers.”

“They understand that securing a promotion is extremely difficult and that advancing through the ranks is challenging. So, they are very cautious. Yet incidents still happen, and they continue to maintain and reinforce themselves as a structure of power,” Raji said.

“This struggle, this conflict with power, the conflict that ordinary people face, particularly in the political sphere, exists everywhere in the world. Think about it: if anything were to occur to Narendra Modi, it’s plausible that it might be a result of deep state orchestration. We witnessed the assassination of John F. Kennedy; similarly, if Donald Trump becomes intolerable to the CIA or the Pentagon, they could take drastic measures against him as well,” Ali Ar Raji told One-man Newsroom.

“Such events occur globally. However, democratic states create mechanisms, institutions, checks, and balances to keep power in check. Ultimately, it is the responsibility of politicians to uphold these systems,” Raji added.

How state power silences truth-tellers

At that May 3 event, this reporter asked the Press Secretary, “For a long time in our country, we often avoided questions about the military and military intelligence agencies. The media rarely covered these topics. However, under the current government, there has been an increase in writing about these topics, and even more will likely be. Do you think that when a different political government takes power, discussions about these issues will fade away again, returning to how things were before?”

In response, Shafiqul Alam said, “To ensure that this does not happen again, there should be even more writing. Everyone should write about what our secret agencies have done during these times, what ugly things they were involved in. We have a moral responsibility to do this. Every news outlet should write about it, so we don’t forget.”

“If we stop writing, if things go silent again, they will tighten their grip once more. When another government comes, they’ll sit on our necks again. And then they will say that everything you’ve seen or reported is against national security, against sovereignty. They will use that to silence everyone,” Shafiqul added. “Everyone should speak up about this. We must ensure that we don’t forget. The more we write about these, the stronger our media freedom will be,” this is what the most talked-about official of the interim government said.

Journalist Tasneem Khalil is listening to Nahid Islam, a leader of the July Movement and the convenor of the National Citizens’ Party (NCP).

📷 Sharif Khiam Ahmed

There is no negative coverage of the military or its officers in mainstream Bangladeshi media, Tasneem notes; this unwritten censorship has been in place for a long time. He said, “It’s a British colonial legacy. The British had laws that prohibited writing about military personnel. That continuity exists in the Bangladesh law.”

“The military in Bangladesh strongly advocates for the confidentiality of its activities, emphasizing the importance of national security and stability in maintaining order. That is most harmful to them. If the military had kept public reporting and criticism open, the military’s current exalted position might not have arisen,” Tasneem told One-man Newsroom.

He added, “In Bangladesh, it is evident that a major in the army, a relatively junior position at the local level, wields significant influence. When he enters a room, even the District Commissioner and others stand up for him; this has become the norm.”

Analysts emphasized that shifts in political power can offer valuable opportunities for reporting on political parties; however, the pervasive military influence in Bangladesh often undermines these efforts, complicating adequate coverage. But Bangladesh is witnessing now, following Hasina’s fall in 2024, an unprecedented situation; people are speaking out and writing against the army.

Ali Ar Raji told One-man Newsroom, “Some journalism is now happening that challenges the whole power structure. People are speaking out. Various things are leaking in different ways. Some former military officers are speaking from abroad. Even influential social media personalities like Pinaki Bhattacharya are saying things that force the military to respond.”

According to him, “We need to evaluate how to limit the political power of the military and ensure they fulfill their intended role in a democratic system. Even now, when we listen to the army chief, his tone, demeanor, and expressions of ambition for the country and the state do not convey the attitude of a public servant. Instead, he sounds like the state’s owner.”

“In other words, the opinionated side of journalism, commentary-based journalism, is now happening regarding the military, because they are in a vulnerable position. Suppose the military regains control and re-establishes itself as a political force. In that case, you will no longer be able to do this. In Bangladesh, who holds political power determines what journalism is possible,” Raji said.

“As long as this mentality persists, journalism will continue to face challenges. This situation will only improve if politicians take the risk to open up the process and hold the military accountable to the public,” Ali Ar Raji added.

Referring to Bangladesh’s political structure, the academic said, “Our politics has never broken free from the conventional centres of power, the military, the police, and the secretariat. It’s not only the military. Have we ever been able to report freely on the Sheikh or Zia family? That’s the bigger context. Even in a district town, have journalists been able to report on the local MP? Has it been possible for anyone? If someone did, could he retain his press club membership? Could he even continue living in that town?”

“So, the problem is not just with the military, whoever holds power, and has the capacity to chase you; in Bangladesh, you cannot report against them,” Raji said. He stated, “At the heart of my message is this: journalism must be recognized as an essential institution in any democratic society, that thrives despite the ongoing struggles for democracy. Journalists have the responsibility to strengthen democracy, institutionalize it, and promote its freedoms.”

The torture and unforgettable suffering

During the DGFI interrogation, Tasneem was asked, “You weren’t even studying journalism; what kind of journalist are you?” He recalled, “At that time, the government was an army-led regime, effectively a military rule in disguise. I was likely the first to label it as such when I was around 25 or 26 years old.”

“Unfortunately, many senior journalists and editors in my country were hesitant to discuss these issues openly. Even the most courageous tended to speak in such polished English that you forgot your own backgrounds,” Tasneem added, “Their language was incredibly refined. Perhaps one or two expressed their thoughts more directly, but I was the one who articulated them clearly. I made this point in several interviews, including a couple of comments in The Washington Post.”

Four months after the army-backed caretaker government took power on 11 January 2007, DGFI took Tasneem into custody from his Central Road home on 11 May. At the time, he was working with the Daily Star, CNN, and Human Rights Watch (HRW) and was a regular blogger.

Tasneem stated, “What I experienced was primarily detention and torture. Before that, I had already been reporting on these issues, and afterwards, I continued to do so. In a sense, my own experience turned into an internal case study for me.”

At Netra News’s Dhaka office, Tasneem Khalil meets survivor Michael Chakma to document his experience of enforced disappearance and secret detention at Aynaghar. March 2, 2025.

📷 Sharif Khiam Ahmed

“Torture leaves deep trauma,” he said. “According to my Swedish psychiatrist, my trauma was decreased by my journalistic mindset. She noted that I continued my journalism work, even while enduring torture. That’s helped me to overcome my trauma, and this is true.”

“With a blindfold over my eyes and my hands restrained, I suffered severe beatings; despite the pain, my mind stayed sharp. I noted each blow: ‘He hit me on the right, then on the left.’ I observed how they tortured, forcing the victim to sit on a bench,” Tasneem said, “I thought of Cholesh Ritchil, a Mandi leader from Madhupur, Tangail, who had been tortured to death not long ago. I had interviewed a survivor from that incident. All these thoughts flooded my mind as I processed the experience.”

Tasneem said, “For a long time, I had been covering military abuses as a journalist. I was collecting more information, even while under their detention. I had intended to write a report. Later, that is what happened.”

Tasneem said, “What I understood was that they were angry with me; their anger was that I was a junior journalist. I don’t belong to the Dhaka elite. My family home is not in Gulshan, Banani, or Baridhara. I’m from a small town. Where did I get the courage to speak against the country’s armed forces, day after day? It was not in my personal interest.” He continued, “I spoke up for hill people’s rights, for Ahmadis, and wherever military abuses occurred, I spoke up. Their objection was: Who are you? That was the main message: how did you get so much courage?”

“At that time, nobody really talked about what was happening in Bangladesh. The biggest supporter of that military-backed government was the Awami League, led by Sheikh Hasina. She said it was the fruit of our movement. People discussed ‘reform,’ but the reforms we later witnessed were quite different,” Tasneem added.

The editor of the Daily Star reported that his detention was a result of the content posted on his blog, ‘tasneemkhalil.com.’ However, Tasneem claims that the DGFI approved everything Mahfuz Anam noted at the time. Mahfuz himself later suffered for publishing many DGFI-verified claims without checking during the army-backed government.

Tasneem said, “At that time, no one in Bangladesh dared to speak openly about what was actually happening. And the biggest supporter of that military-backed government was the Awami League, meaning Sheikh Hasina. She even said this caretaker setup was the ‘fruit of their movement.’ Today, none of them talks about it.”

Operation Clean Heart, which changed Tasneem

“Tasneem Khalil’s courage does not come from any extraordinary source. I believe my strength comes from understanding that journalism is one of the most powerful tools in modern society. It empowers individuals to have a significant impact. If I practice ethical and impactful journalism, I will naturally become one of the most influential people in society. There’s nothing particularly heroic about this; it’s simply a matter of calculation,” the journalist explained.

Tasneem never wanted to be a journalist. He said, “I had no real desire to become a journalist because both my parents were journalists, especially my father. Given their history, I never wanted to be a journalist; it was at the bottom of my list of choices.”

“At that time, I was at North South University. We had an English Club. News Today, which had not yet begun, had contacted the club; they wanted a few feature writers for their weekend magazine. Through that connection, I joined News Today as a feature writer. That’s how my journalism began, to earn pocket money. There was no other reason,” he added. But very soon his outlook changed. “At some point, I realized journalism is a compelling profession. And that is what I wanted to become — powerful and necessary.”

Tasneem’s viewpoint was heavily influenced by “Operation Clean Heart,” a controversial initiative from October 16, 2002, to January 9, 2003, marked by many extrajudicial killings. A particular event during this operation profoundly transformed Tasneem’s understanding of justice and morality.

He recalled, “I was then working at News Today as a regular feature writer. Operation Clean Heart had begun. From the Moghbazar intersection, News Today’s office is on one way, and the Taj Hotel, which still exists, is on the other; behind it, there was a large residential hotel. That was actually a brothel, an illegal red-light zone.”

“During Operation Clean Heart, the angels, that is, the army, raided various places. One evening, as I walked to the office, I witnessed a raid on that hotel. Army vehicles arrived. It was a hellish scene. Big, tall young men were grabbing each woman by the hair, by their clothes, or by the neck, dragging them out of the hotel. Soldiers were throwing them into pick-up vans.”

“Suddenly, I saw a woman, alone, trying to escape by clinging to a cornice from a window on the sixth or seventh floor. That day, I saw both the powerlessness in the face of power and, at the same time, the courage. ” It left a deep impression on me,” he said. “At that moment on the street in Dhaka, I decided my reporting specialization would be police power.” I have been doing that ever since. After that incident, I had to prepare myself.”

“For example, Police Regulations, I mean the Police Regulations of Bengal, I literally memorized almost the entire book. Studying various laws and regulations helped me identify key areas to focus on for producing an effective investigative report.”

Besides News Today, he worked for New Age and the Daily Star. For a time, he worked at Amader Shomoy with Naimul Islam Khan, the fugitive press secretary of a former prime minister. He also worked at an advertising firm called Adcom. Through his work on RAB, he first joined Human Rights Watch’s research team.

Tasneem Khalil launched Netra News on December 26, 2019, with a four-member team, including British investigative journalist David Bergman, who played a key role in its founding. As the editor of the English edition in its early years, Bergman shaped the outlet’s editorial vision and international reach. His extensive experience in Bangladeshi politics and media freedom helped establish Netra News as a credible platform for in-depth investigative reporting from exile.

The site was blocked in Bangladesh shortly after its first report, allegedly by the intelligence services. However, it became accessible again following Hasina’s departure on August 5, 2024. Tasneem, who is returning to Bangladesh, stated that he will not only practice public-interest and investigative journalism but also teach it. Netra News has already partnered with BRAC University to launch a course on this subject.

Tasneem Khalil was in his inaugural class at BRAC University, inspiring students to explore the vital field of public-interest journalism.

Killing of Anti-India Leader Deepens Dhaka–Delhi Rift

The death that changed Bangladesh’s political weather.

Understanding the New York Times vs. Shafiqul Alam Debate

Bangladesh faces rising extremism amidst economic and social progress.

Netra News Exposes Army-NCP Tensions in Bangladesh

Independent media vital for Bangladesh’s democracy amid military tensions.

Leave a comment