📷 CAO

Newsman, Dhaka

The Commission of Inquiry on Enforced Disappearances (COIED) inquiry establishes that enforced disappearance in Bangladesh had a significant transnational dimension, particularly involving India.

Their final report, titled “Unfolding the Truth: A Structural Diagnosis of Enforced Disappearance in Bangladesh,” provides a harrowing look into how the state’s apparatus for erasing critics extended far beyond its own borders.

In Chapter 10, the Commission shifts its lens from domestic torture cells to the “Foreign Nexus,” identifying enforced disappearance as a crime that relied heavily on international collusion.

According to the report, “Enforced disappearance constitutes an inter-state crime due to its cross-border dimensions.” The Commission’s inquiry found that “such cross-border transfers or exchanges of captives would not be possible without the collusion or active cooperation of Border Guard Bangladesh (BGB) and the Indian Border Security Force (BSF).”

This structural cooperation transformed the sovereign borders of Bangladesh into a gateway for illegal renditions, where the state’s critics were systematically handed over to foreign custody or retrieved from across the border in total secrecy.

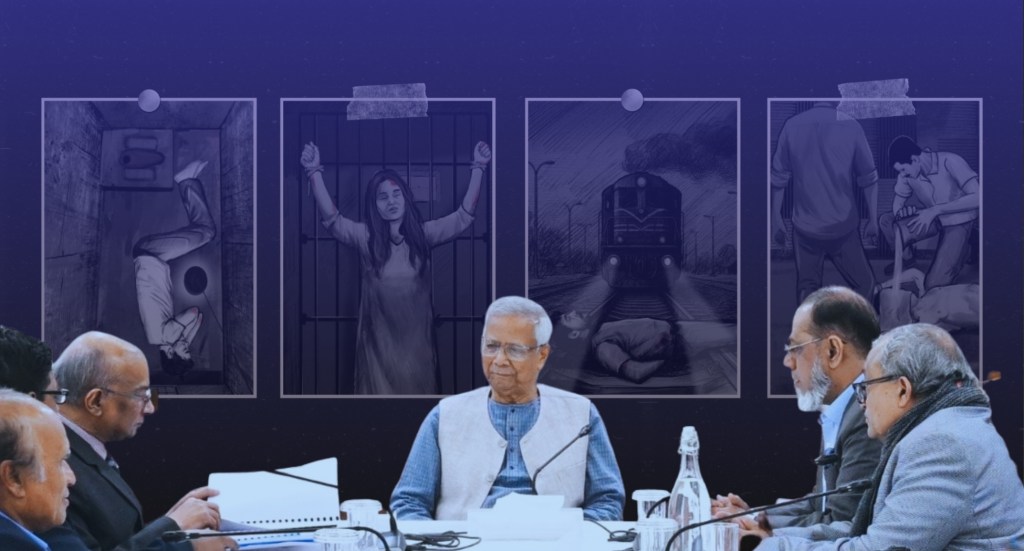

On January 13, the COIED published its final report on its official website. Commenting on the release, the Chief Adviser’s Press Wing stated that enforced disappearance in Bangladesh over the last 15 years was not an isolated incident; instead, it was a well-planned, institutional, and politically motivated crime.

This publication coincides with significant remarks from Indian Army Chief General Upendra Dwivedi regarding the current situation in Bangladesh. “It is important for us to understand what kind of government is in place in Bangladesh. If it is an interim government, we need to see whether the actions it is taking are meant for the next four-five years, or only for the next four-five months,” he said.

The topic of Indian involvement emerged prominently on June 19, 2025, capturing significant attention and dialogue. During a press conference, Commission President Justice Moyeenul Islam Chowdhury stated, “Even if Indian intelligence agencies are involved in the disappearances, we have nothing to do with them because it is outside our jurisdiction.”

The COIED’s final report now thoroughly outlines India’s involvement, evolving from a previously held notion of jurisdictional limits to an in-depth examination that clearly reveals the foreign ties at play.

The India connection and illegal renditions

The depth of the security relationship between the former Awami League regime and Indian intelligence agencies is detailed with alarming specificity in Chapters 10.1 and 10.2.

The report notes: “Enforced disappearance constitutes an inter-state crime due to its cross-border dimensions… The Commission’s inquiry finds that such cross-border transfers or exchanges of captives would not be possible without the collusion or active cooperation of BGB and the Indian Border Security Force (BSF)” (Page 61).

It further details that: “This relationship extended beyond rhetoric and translated into tangible joint operations, cross-border coordination, and illegal renditions. In several testimonies, victims describe being handed over from Indian custody to Bangladeshi intelligence, and vice versa” (Page 152).

Testimony from victims and security personnel paints a picture of a well-oiled machine for “Captive Exchange.” One soldier from the Rapid Action Battalion (RAB) Intelligence Wing provided a chilling account of an exchange at the Tamabil border, stating: “We went to the border area and exchanged those two captives with the Indians. We received two captives from India in return” (Page 152). The report indicates that on another occasion, two captives were killed on the roadside after the exchange, highlighting that the rendition system often led to extrajudicial executions.

The COIED identifies specific high-profile cases as emblematic of this rendition system. It mentions the case of BNP leader Salauddin Ahmed as a “stark example of cross-border rendition involving India” (Page 61). Additionally, it cites the case of Shukhoranjan Bali: “Another highly publicized case is that of Shukhoranjan Bali, a witness abducted from Bangladesh Supreme Court premises, who resurfaced subsequently in an Indian jail” (Page 152).

These actions allowed the state to “outsource” the disappearance, later claiming the victims were merely “trespassers” in a foreign land. The report clarifies the protocol: “Testimony before the Commission reveals that RAB usually notified BGB before conducting cross-border renditions, specifying border locations where their vehicles would cross” (Page 61).

Foreign Presence in Secret Detention Centers

Perhaps most disturbing is the evidence of foreign intelligence officials operating within Bangladesh’s secret detention network. The report documents that “Individuals speaking foreign languages, including Hindi, also visited prisoners at secret detention sites” (Page 155).

Specifically, in the case of Hummam Quader Chowdhury, the report states: “Hummam Quader Chowdhury describes hearing Hindi-speaking people outside his cell inquiring about the condition of his captivity, such as: When was he picked up? Has he given any information? What interrogation has been done yet?” (Page 152).

Another victim (Code BDIJ130) reported being interrogated by officials from “Delhi “Headquarters, specifically regarding his social media posts about “torture of Kashmiri Muslims” (Section 10.1). These revelations suggest that “Aynaghar“, and other secret sites were part of a regional network of repression, allowing foreign actors access to political prisoners without legal oversight.

Bangladesh: Where the State Erased Its Critics

Enforced disappearances were systematic and politically motivated.

The Journalist the Generals Couldn’t Silence

From torture and exile to exposing Bangladesh’s military deep state.

Western actors and the authoritarian bargain

While India‘s proximity played a direct operational role, Chapter 10.3 addresses the more nuanced but equally critical involvement of Western actors. The report explores how the global “War on Terror” provided a convenient cover for the regime to build its disappearance infrastructure.

Western nations offered training and advanced surveillance support under the pretext of counter-terrorism, creating an “authoritarian bargain.” The report reveals that the AL regime often repurposes these tools to track and abduct political dissidents, journalists, and activists, undermining the democratic values these nations claim to uphold.

The Commission argues that “The portrayal of the regime as an indispensable bulwark against Islamist extremism… created an environment where international partners, particularly India, provided ‘tacit tolerance or even active backing’ for these systemic abuses” (Page 159).

Ultimately, the report asserts that these foreign individuals’ presence, while not always involving direct physical abuse, “gave legitimacy to a broader system of enforced detention” (Page 159).

The Commission concludes that the “Foreign Nexus” was a key pillar in maintaining the culture of impunity that lasted for over fifteen years. By working with foreign agencies and using cross-border renditions, the state created deniability. A critic abducted in Dhaka could “resurface” in an Indian jail, enabling the Bangladeshi government to deny any involvement in their disappearance.

This transnational network not only removed critics but also weakened legal protections for citizens. The report highlights that the silence and cooperation of international security partners were key to understanding this crime.

To understand the full extent of the state’s role in these disappearances and the complicity of international actors, readers are encouraged to read the full report.

UN backing for institutional reform

The Commission’s findings gained international prominence during a January 13 call between Chief Adviser Professor Muhammad Yunus and UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Volker Türk. Professor Yunus formally shared the final report with the UN human rights chief, describing it as a “crucial document” that will play a pivotal role in ensuring accountability and justice for the victims of enforced disappearances during the autocratic regime from 2009 to 2024.

High Commissioner Türk praised the Commission’s work and reaffirmed the UN’s commitment to supporting the transition, emphasizing that establishing a “truly independent” National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) is essential to carry forward the legacy of this investigation.

Professor Yunus assured the UN official that the NHRC would be reconstituted before the upcoming February 12 elections, ensuring that the institutional reforms necessary to prevent a return to the era of disappearances are firmly in place before the interim government concludes its mandate.

Leave a comment